I have been wanting to dive into algebraic cryptanalysis of the modern cryptographic primitives. Almost all of PQC and FHE is based on mathematical lattices, and hard problems based on it. For those who are not aware, cryptanalysis is a branch of cryptology, where we try to find weaknesses and vulnerabilities in a given cryptosystem. For this, we must have a deep and conceptual understanding of the system itself in order to try and find such compromises.

Definition of a Lattice

In simple terms, a lattice $\mathcal{L}$ is a collection of points in $n$-dimensional space with a regular, repeating structure. Mathematically, we define it using a basis.

If we have $n$ linearly independent vectors, $\{b_1, \cdots, b_n\}$ in $\mathbb{R}^n$, the lattice generated by this basis is the set of all integer linear combinations of these vectors: $$ \mathcal{L} = \{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_ib_i : x_i \in \mathbb{Z}\}$$

Now, one might say that it’s a vector space over the field of real numbers. But note that we have constrained our $x_i$s to integers only, in case of a vector space, these could have been any real number. This constraint creates a discrete grid of points.

Basis Matrix and Determinant

We usually represent the basis as a matrix $\mathcal{B}$, where each column is a basis vector $b_i$.

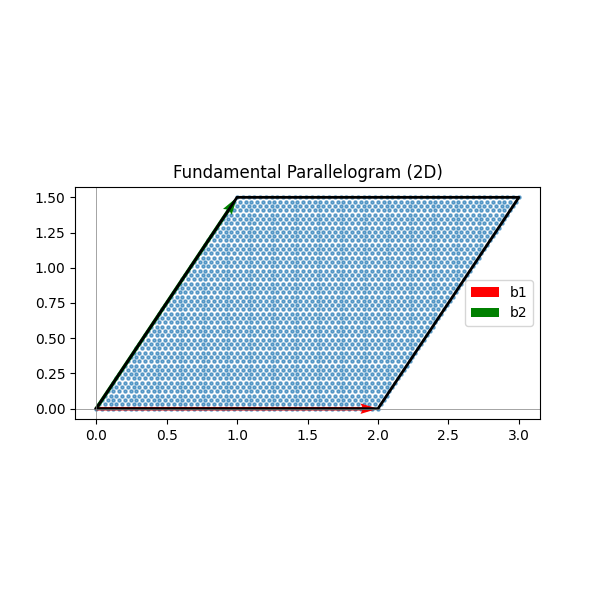

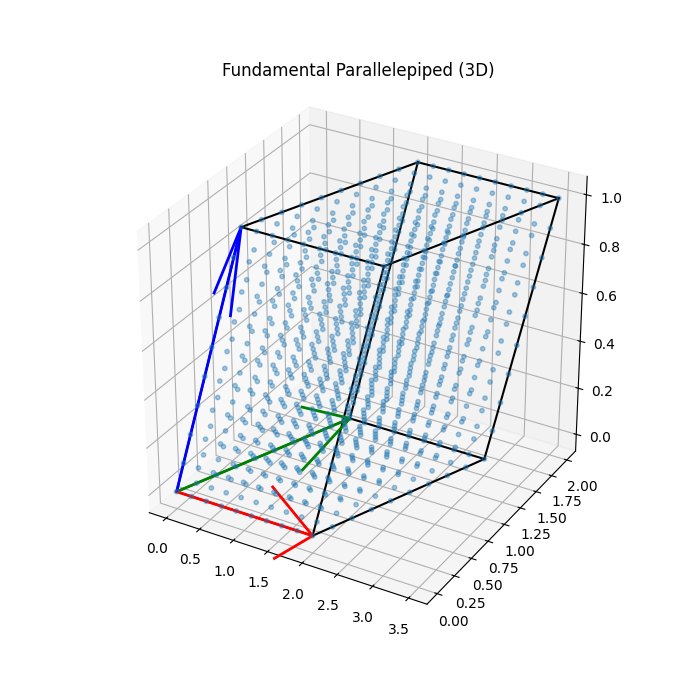

The Fundamental Parallelpiped

If you take the basis vectors, and “fill in” the space between them (using coefficients between 0 and 1), you get a shape called the fundamental parallelpiped, denoted as $\mathcal{P}(\mathcal{B})$: $${P}(\mathcal{B}) = \{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} a_ib_i : a_i \in [0, 1)\}$$

Below are two figures visualizing the same fundamental parallelpiped in 2D and 3D, and for very obvious reasons, I cannot present a visualization of any higher dimension.

The Determinant (Volume)

The volume of this shape is an invariant of the lattice called determinant, denoted $\text{det}(\mathcal{L})$. It represents the “inverse density” of the points. For a full-rank lattice: $$\text{det}(\mathcal{L}) = |\text{det}(B)|$$

“Good Basis” vs “Bad Basis” Problem

This is the core of lattice-based cryptography. A single lattice can be represented by infinitely many different bases.

- Good Basis: Vectors are relatively short and nearly orthogonal (perpendicular). This makes it easy to find the point in the lattice closest to some target. I’ll elaborate more on this later.

- Bad Basis: Vectors are very long and meet at extremely sharp angles. This makes the lattice look like a chaotic “haystack,” hiding its structure.

In a cryptosystem, the Secret Key is usually a Good Basis, and the Public Key is a “randomized” Bad Basis. Cryptanalysis is essentially the attempt to turn that Bad Basis back into a Good one.

Minkowski’s Theorem

This is a core theorem of lattices. It is a theorem which if one gets the proper intuition of, gets great insights into analysis of lattice structures. It essentially guarantees that if a lattice has a certain volume, there must exist a non-zero short vector within a specific bound. To get a good intuition of this short vector, imagine a lattice on the 2D plane with the fundamental parallelopipeds sketched throughout, considering all the normal vectors from the origin to these edges, the one having the least “length” is labelled as the shortest vector.

In cryptanalysis, one should not be afraid of formalism, sooo, take a look below:

Theorem (Minkowski’s Theorem)

Let $\mathcal{L}$ be a full-rank lattice in $\mathbb{R}^n$ with determinant $\text{det}(\mathcal{L})$. If $S \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ is a convex, centrally symmetric set with $\text{vol}(S) > 2^n$, then $S$ contains at least one non-zero lattice point $v \in \mathcal{L} \setminus \{0\}$.

How does this statement map to the explanation I gave above? Well, imagine placing the lattice points in space and drawing the fundamental parallelpiped around each point, so that space is perfectly tiled. Now center a symmetric “ball” (or any convex shape) at the origin and slowly expand it. If this shape becomes large enough compared to the volume of a single parallelpiped, it is impossible for it to cover only the origin, there simply isn’t enough room to avoid capturing any other lattice point. When this happens, the vector from the origin to that point is a short lattice vector. Minkowski’s theorem makes this intuition precise: the volume of the lattice directly limits how far the nearest non-zero lattice point can be. For a convex set, it is the set of points, where each line connecting any two points lies completely inside the curve traced by the set.

Now, let’s look into the proof. First, let’s have a look at the following lemma, or the Blichfeldt’s Theorem, which if you really see, is nothing but the pigeon-hole principle.

Theorem (Blichfeldt’s Theorem)

If a set $S’$ has a volume strictly greater than the determinant of the lattice ($\text{vol}(S’) > \text{det}(\mathcal{L})$), then there must be at least two distinct points $z_1, z_2 \in S’$ such that their difference $z_1 - z_2$ is a lattice point.

To get some formal intuition, imagine a random lattice, the best visualization is the 2D plane tiled with the same parallelpiped throughout. Now imagine a cloth with area greater than the area of a single parallelpiped, note to avoid confusion, that I am referring to the volume of the lattice as area in this case. Instead of working with normal cartesian coordinates, any point is identified by which parallelpiped the point lies in and its position relative to that particular parallelpiped only. If we just place this cloth (set) over this lattice, we shall have at least two points with same internal relative coordinates with different parallelpiped coordinates, now the global vector joining these two points, will just be a lattice vector with some offset with respect to the grid lines.

Proof (Blichfeldt’s Theorem)

Let $\mathcal{L} \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ be a full-rank lattice, and let $F$ be a fundamental domain of $\mathcal{L}$ with volume

$$

\operatorname{vol}(F) = \det(\mathcal{L}) = V.

$$

Let $S’ \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ be a measurable set with volume

$$

\operatorname{vol}(S’) = V’ > V.

$$

Every point $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ can be written uniquely as

$$

x = \alpha + \beta,

$$

where $\alpha \in \mathcal{L}$ is a lattice vector identifying the lattice cell containing $x$, and $\beta \in F$ is the local position of $x$ within that cell.

Define the mapping

$$

\pi : \mathbb{R}^n \to F

$$

by reducing points modulo the lattice:

$$

\pi(x) = \beta.

$$

This map translates each point of $S’$ into the reference cell $F$ without changing volume.

Since translations preserve volume,

$$

\operatorname{vol}(\pi(S’)) = \operatorname{vol}(S’) = V’ > V = \operatorname{vol}(F).

$$

However, $\pi(S’) \subseteq F$, so this is only possible if the map $\pi$ is not injective.

Hence, there exist two distinct points $P_1, P_2 \in S’$ such that

$$

\pi(P_1) = \pi(P_2) = \beta.

$$

Writing

$$

P_1 = \alpha_1 + \beta \quad \text{and} \quad P_2 = \alpha_2 + \beta,

$$

with $\alpha_1, \alpha_2 \in \mathcal{L}$, we obtain

$$

P_2 - P_1 = \alpha_2 - \alpha_1 \in \mathcal{L}.

$$

Thus, the difference of two distinct points in $S’$ is a nonzero lattice vector, completing the proof.

Proof (Minkowski’s Theorem)

With the above theorem in our hands, let’s see the proof of the core theorem.

Let $\mathcal{L} \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ be a full-rank lattice and let $S \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ be convex and centrally symmetric with

$$

\operatorname{vol}(S) > 2^n \det(\mathcal{L}).

$$

Define the scaled set

$$

S’ = \frac{1}{2} S.

$$

Then

$$

\operatorname{vol}(S’) = 2^{-n} \operatorname{vol}(S) > \det(\mathcal{L}).

$$

By Blichfeldt’s Theorem, there exist two distinct points

$$

x_1, x_2 \in S’

$$

such that

$$

x_1 - x_2 \in \mathcal{L}.

$$

Since $S’ = \frac{1}{2} S$, we have $2x_1, 2x_2 \in S$. Therefore,

$$

2(x_1 - x_2) = (2x_1) - (2x_2).

$$

Because $S$ is centrally symmetric, $-2x_2 \in S$, and because $S$ is convex, the sum of two points in $S$ lies in $S$. Hence,

$$

v := 2(x_1 - x_2) \in S \cap \mathcal{L}.

$$

Since $x_1 \neq x_2$, we have $v \neq 0$, proving that $S$ contains a non-zero lattice point.

QED

Now, one might wonder, why did we only assume $\operatorname{vol}(S) > 2^n \det(\mathcal{L})$ and not any arbitrary factor? Well, the constant $2^n$ is not arbitrary, it is optimal. To see why, observe that shrinking a set by a factor of two in each dimension scales its volume by $2^{-n}$. The proof of Minkowski’s theorem relies on shrinking $S$ to

$$

S’ = \frac{1}{2} S,

$$

so that

$$

\operatorname{vol}(S’) = 2^{-n} \operatorname{vol}(S).

$$

The hypothesis $\operatorname{vol}(S) > 2^n \det(\mathcal{L})$ ensures that

$$

\operatorname{vol}(S’) > \det(\mathcal{L}),

$$

which is precisely the condition needed to apply Blichfeldt’s Theorem.

Crucially, this bound cannot be improved in general. For example, in the lattice $\mathbb{Z}^n$, the centrally symmetric cube

$$

(-1,1)^n

$$

has volume $2^n$ and contains no non-zero lattice points. Any smaller constant would allow counterexamples.

Thus, $2^n$ is the smallest universal threshold that guarantees the existence of a non-zero lattice vector.

Now, why is this theorem sooo important in post-quantum cryptology? For the designer of the cryptosystem, the theorem defines the “safety zone.” It tells us exactly how small we can make our errors (noise) while still ensuring that the secret key remains unique and theoretically recoverable.

For a cryptanalyst, the theorem is a guarantee of success, given enough time. It proves that the “shortest vector” is mathematically bound to exist within a specific radius. However, there is a catch, which ensures the lattice-based security: Minkowski’s Theorem proves the vector exists, but it doesn’t give us a map to find it. In high dimensions ($n > 500$), even though we know a short vector is “hiding” in that convex set, finding it is like searching for a needle in a hyper-dimensional haystack.

Let’s end this part here. This should be enough for us to formally understand the hard problems of lattice and reverse engineering, or solving those problems.

PS: I am an undergrad student only trying to make sense out of all the math behind the modern crypto, if you find any error, logical, formatting, language, etc… feel free to inform me via email or twitter.

peace. da1729